CHANGES IN STYLE OF LOCAL SANDSTONE BUILDINGS - 1868 to 1934

Early quarrying of red sandstone had left the Potsdam area populated with small buildings and homes, most of which were constructed in the same slab-and-binder style used in the 1835 Trinity Church. That era had faded by the 1850s, but sandstone quarrying was revived in the aftermath of the Civil War. It was aided by new orders for construction projects, the growth of a network of railroads throughout the North Country and the use of steam-powered quarrying machinery.

The quarrying of Potsdam Sandstone became consolidated into large-scale commercial businesses with two major companies operating on the banks of the Raquette River. The Red Sandstone Company owned the old Parmeter quarry and other sites just north of Hannawa Falls. The company was a consortium of local businessmen that included General Edwin Merritt, the politician-philanthropist of Civil War fame whose home still stands on the corner of Leroy and Garden streets. The Clarkson family owned the quarries closer to Potsdam—an early one had opened in the 1820s on the west side of the river near the present Sugar Island dam, and another on the east side in 1877 .

Susan Omohundro has labeled the period from 1868 to 1934 as the Industrial Era of Potsdam Sandstone quarrying. She recognized fifteen major public buildings that were constructed of red sandstone at this time. They include the Presbyterian Church, Potsdam (1868); the former Herring-Cole library (1869, addition in 1902) on the campus of St. Lawrence University, Canton; Potsdam’s water plant on Raymond Street (1871, addition in 1906); Zion Episcopal Church, Colton (1883); Trinity Church—the chapel in 1884 and the north façade of the nave in 1886; the downtown Cox Building (1888, housing Maxfield’s Restaurant in 2006); Clarkson University’s Old Main (1896); Bayside Cemetery Lodge and Gatehouse (ca. 1900); Hannawa Falls Power Plant (ca. 1900); St. Mary’s Catholic Church (1900); the Clarkson Office Building (1901, across Maple Street from Trinity Church); the Penn Central train depot (1914, housing Mama Lucia’s Restaurant in 2006); Snell Hall (1917) on Park Street opposite the Civic Center; and the assemblage of sandstone buildings of the Potsdam Museum and Civic Center (1934).

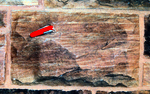

By the mid nineteenth century, rough ashlar masonry was favored by local architects. It consisted of large rectangular-hewn blocks, some laid in long horizontal rows and some not. The sandstone is very hard, thanks to quartz grains cemented by quartz, and the hardness often is uniform in all directions. Workers using a hammer and a broad chisel could trim the face of a block and leave curved or conchoidal fractures—grooves shaped like the bowl of a spoon. The result was a coarse surface texture that looked better from a distance than up close (Fig. 15).

Figure 15. A block of ashlar-cut Potsdam sandstone showing conchoidal fractures (curved grooves). The grooves were produced by striking with a broad chisel. By the 1850s, ashlar masonry had replaced the slab-and-binder technique previously used for this hard and brittle sandstone. From the west wall of Trinity’s 1955 parish hall. Pocket knife for scale.

The editors of a noted science and mechanics magazine sent reporters north to Potsdam to examine the sandstone quarries. The January 7 and 21, 1893, issues of The Weekly Journal of Scientific American featured lithographs, probably made from photographs, of quarries along the Raquette River. Several quarries were large and deep by this time, including the No. 1 Quarry of the Potsdam Red Sandstone Company. The quarry site is located on private property about one mile north of Hannawa Falls on the West Hannawa Road (Figs. 16, 17). It was owned by a consortium of local businessmen including General Edwin Merritt, the politician-philanthropist of Civil War fame. Note the tall derricks with inclined booms. Each boom could swing in a half-circle arc over the quarry floor and lift large blocks from the pit (Figs. 18, 19). Undoubtedly, a temporary derrick and boom had been erected on Fall Island during the construction of Trinity Church.

Figure 16. An arrow points to the site of the Number 1 Quarry of the Potsdam Red Sandstone Company, now a deep water-filled pit on private property (see Fig. 17). Other quarries lay next to the Raquette River, including one at the Hannawa Falls dam and power plant. Note the location of the Parmeter family cemetery next to the West Hannawa Road (top of map). The Parmeters were among the first to quarry the sandstone. Reproduced from the Potsdam and Colton 1:24,000 scale topographic maps.

Figure 16. An arrow points to the site of the Number 1 Quarry of the Potsdam Red Sandstone Company, now a deep water-filled pit on private property (see Fig. 17). Other quarries lay next to the Raquette River, including one at the Hannawa Falls dam and power plant. Note the location of the Parmeter family cemetery next to the West Hannawa Road (top of map). The Parmeters were among the first to quarry the sandstone. Reproduced from the Potsdam and Colton 1:24,000 scale topographic maps.

Figure 17. SUNY Potsdam students examine the No. 1 quarry, now filled with water to a depth of about 80 feet. The water level fluctuates with the level of the adjacent Raquette River (not shown here).

Figure 18. View southward in 1892-3 over the Number 1 Quarry (now flooded) of the Potsdam Red Sandstone Company. The Raquette River flows from upper right to lower left and turns the water wheel located at the walking bridge. Note the derricks, booms and numerous outbuildings for stone cutting and machine repair. The gentleman and lady (lower left) are gazing over a capitalistic enterprise of considerable proportions. Reproduced from Scientific American magazine, 1893.

Figure 18. View southward in 1892-3 over the Number 1 Quarry (now flooded) of the Potsdam Red Sandstone Company. The Raquette River flows from upper right to lower left and turns the water wheel located at the walking bridge. Note the derricks, booms and numerous outbuildings for stone cutting and machine repair. The gentleman and lady (lower left) are gazing over a capitalistic enterprise of considerable proportions. Reproduced from Scientific American magazine, 1893. Figure 19. View north from inside the quarry toward the elevated ground occupied by the couple in Fig. 18. Steam power drills are in use, but workers in the lower right corner are using hand tools to loosen slabs along bedding planes. Note the stairsteps of cut rock. Loose glacial sediments occur in the bluff (far left), and one worries about the stability of General Merritt’s cottage on top. Reproduced from Scientific American magazine, 1893.

Figure 19. View north from inside the quarry toward the elevated ground occupied by the couple in Fig. 18. Steam power drills are in use, but workers in the lower right corner are using hand tools to loosen slabs along bedding planes. Note the stairsteps of cut rock. Loose glacial sediments occur in the bluff (far left), and one worries about the stability of General Merritt’s cottage on top. Reproduced from Scientific American magazine, 1893.

Figure 20. The undershot water wheel at the walking bridge across the Raquette River in Fig. 18. The heavy weight mounted in the center of the photograph was lowered, and the wheel was lifted above the surface. Logs could pass under the wheel without damage. Reproduced from Scientific American magazine, 1893.

Scientific American magazine also reported on a new invention by the sandstone company—a unique paddle wheel suitable for rivers that were extensively used by lumber companies. The wheel was constructed to rise above the water, when necessary, to permit the passage of logs below (Fig. 20). Lumber companies were operating in the headwaters of the Raquette River, and thousands of logs at Tupper Lake were directed north to Potsdam. It was claimed that the logs did no damage to the wheel. No unusual skills were required for construction of the unique wheel, and “regular employees” of the Potsdam Red Sandstone Company had built this one for $2500. “Irregular employees,” of the company, I presume, just watched. Floating logs were stored and recovered in the quiet backwater behind Trinity Church before being delivered to the sawmills.